Poster for Puccini's Madama Butterfly, depicting the show's violent end. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

This blog post is part II in a series about the history connecting Madame Butterfly to David Henry Hwang’s Yellow Face. To check out part I, click here. To check out the production of Yellow Face premiering on Broadway Oct 1, click here.

David Henry Hwang’s Broadway career started with Madame Butterfly. He did not restage David Belasco’s one-act from 1900 or attempt his own version of Giacomo Puccini’s opera Madama Butterfly (which was based on Belasco’s one-act). No, David Henry Hwang used Madama Butterfly to write his own play; one that turned the opera inside out and forced audiences to confront the rot lurking inside Puccini’s orchestral swells and soprano arias.

David Henry Hwang was born in postwar Los Angeles over fifty years after Madama Butterfly premiered. He was the son of Chinese immigrants who came to America at a time when immigration quotas made it very difficult to move to the country as an Asian (even more difficult than it is today). His father, Henry Yuan Hwang, would go on to found Far East National Bank, the first Asian-American federally chartered bank – though David did not grow up the son of a bank owner. Far East National wasn’t chartered until the 1970s, around the time David graduated high school and started college at Stanford.

David Henry Hwang. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Stanford is where Hwang discovered playwriting, before moving on to the Yale School of Drama, where he cut his studies short because he was already getting produced in New York. His play FOB premiered at The Public Theater in 1980, examining the fault lines separating a second-generation Chinese-American, his first-generation cousin, and the fresh-off-the-boat exchange student from Hong Kong she’s dating. The following year in 1981, FOB won an Obie Award for Best New American Play and Hwang had two additional plays premiere at The Public. The Dance and the Railroad told the story of a pair of Chinese railroad workers in the American West who practice Chinese opera together as they wait out a strike, and Family Devotions was a dark comedy about an evangelical Chinese-American family and a long-lost, atheist uncle from China who drops in on them. This trifecta at The Public established Hwang as one of the most promising young playwrights in the city. By the end of the decade, Hwang’s Broadway premiere would catapult him into mainstream recognition.

Bernard Boursicot's passport photo form the 1960s. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

The genesis for that premiere was the story of Bernard Boursicot, a French diplomat who shared government secrets with his mistress, Shi Pei Pu, while stationed in China. When Boursicot returned to France, Shi followed, and they were both charged with espionage. But that wasn’t even half le scandale. Shi had another secret that was revealed in the trial. Shi was actually a man who had tricked Boursicot into believing he was a woman for the entire length of their twenty-year relationship. He went so far as to adopt an infant in secret that Boursicot believed was his. For his part, Boursicot maintained he never knew Shi was a man: “I thought she was very modest. I thought it was a Chinese custom.”

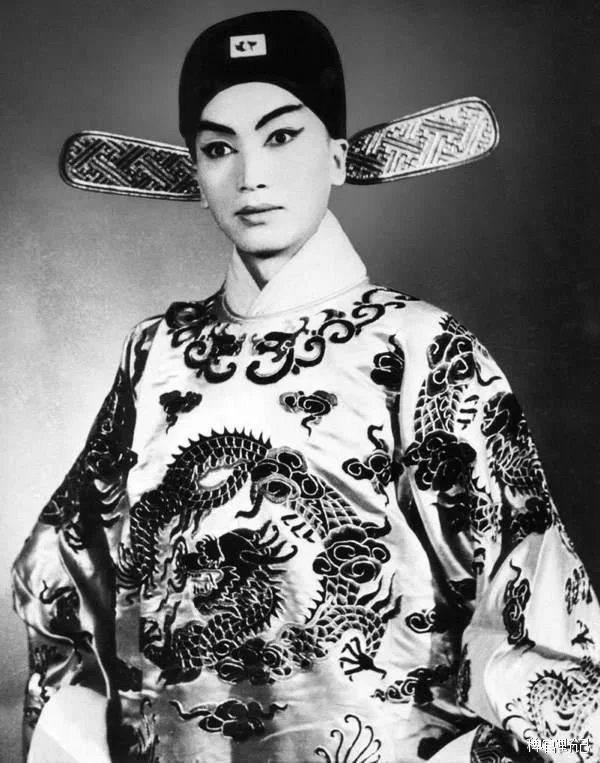

Shi Pei Pu, in a Chinese Opera costume. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

The tabloid scented tale managed to get international press, which was how Hwang found out about it. It made him think of Madama Butterfly.

Madama Butterfly did not originally seem destined to become a classic when it premiered in Milan in 1904. It flopped. So Puccini reworked it and, voila! It vaulted into the opera canon and was performed regularly all over the world for generations, including at New York’s Metropolitan Opera. The Met performed the opera 8 days before Japan attacked the United States at Pearl Harbor, and also 5 months after the United States destroyed Nagasaki with an atomic bomb. (Nagasaki, you may remember, is where Puccini’s opera is set). That is the longest stretch of time New York City has gone without a performance of Madama Butterfly at The Met since the company first played the work in 1907.

Why does Puccini’s work have such staying power, while Belasco’s play has faded into obscurity as a footnote? Well, the opera is certainly much grander and more dramatic. In Puccini’s Act 1 we see Cio-Cio-San (Italian for Cho-Cho-San) arrive at her new house with an entire entourage. We see her wedding with Pinkerton, and we see her evil uncle disown her for converting to Christianity. Pinkerton is a touch more complex; still callous and cowardly, but with a romantic side too. After Cio-Cio-San’s family disowns her at the wedding, Pinkerton leaps into action and kicks the sorry lot out, then comforts Cio-Cio-San before (ahem) consummating the marriage. None of this happens in Belasco’s play.

Of course, Puccini’s gorgeous music is the real reason his work is still performed. Check out the humming chorus he composed to cover the same scene transition I described in last week’s post, Cio-Cio-San’s all-night vigil with her servant and son. Puccini loved this part of Belasco’s play, and it shows.

But underneath the music and the grandiosity, there is a more basic reason Puccini’s work has survived. Madama Butterfly is high opera; everyone speaks fluent Italian. The work would not have survived so widely and so long with Belasco’s original racist dialect. The Italian (che bello!) makes it easier to overlook the parts of the story that haven’t aged so well. Make no mistake, once you’re past the wedding drama of Act 1, the opera and the one-act are basically the same. The Japanese are still backwards, tribal, not to be trusted. Cio-Cio-San is naive to think her marriage is real, ridiculous to think it makes her American, and noble because she sacrifices herself all the same, so that her son can live with his cowardly, good-for-nothing father in America. You wanna know another difference between the opera and the play? In the opera, we learn that Cio-Cio-San is only 15 years old.

Hwang saw these dynamics very clearly for what they were in Madama Butterfly, and he recognized them in the story of Boursicot. Shi Pei Pu had used his fantasies of submissive Asian femininity to manipulate him. Shi Pei Pu “pulled a butterfly,” and M. Butterfly, as Hwang’s play is titled, tells the story of how it all went down.

Hwang wrote M. Butterfly quickly, just six weeks for the first draft. He made it a point not to research the real-life Boursicot saga, and instead used the general facts to trace a fictional narrative across a set of avatars. Bernard Boursicot becomes Rene Gallimard, a French diplomat stationed in Beijing in the 1960s. Shi Pei Pu becomes Song Liling, a Chinese opera performer working in Beijing at the same time. Madama Butterfly is central to their story. Gallimard meets Song when the latter is performing Cio-Cio-San at the German ambassador’s house. Madama Butterfly just so happens to be Gallimard’s favorite opera. And here she is, his own Cio-Cio-San, live and in the flesh. The affair and story unfurl from there, with Puccini’s opera as a framing device the entire way.

M. Butterfly premiered at the National Theatre in D.C. February 1988 and moved to Broadway’s Eugene O’Neill Theatre the following month. John Dexter (whose career straddled both opera and theatre) directed the production with a budget of $1.5 million, “opulent” for a play at the time. The investment paid off. M. Butterfly was a hit in New York, running for over 700 performances. Hwang won the Tony Award for best new play (the first Asian-American to do so) and was honored as a finalist for the Pulitzer Prize in Drama. In 1993, David Cronenberg directed a film adaptation of the play.

An image of M. Butterfly's production set, with BD Wong at top and John Lithgow below. Source: Billy Rose Theatre Division, The New York Public Library.

The production’s success was also due in no small part to its cast, starting with John Lithgow as Gallimard. That’s a name I imagine many readers will recognize. Lithgow’s work has spanned decades, with prominent roles across film, tv, and animation – Lord Farquaad in Shrek, Winston Churchill in The Crown, and Dick Solomon in Third Rock from the Sun, to name a few. Those credits all came after M. Butterfly, but Lithgow was still an established star in 1988, with an academy award nomination, over a dozen Broadway credits, and major roles in popular movies like Footloose and Harry and the Hendersons. It helped to have a talented celebrity in an anchor role like Gallimard, who’s on stage for almost the entire play.

M. Butterfly essentially takes place within Gallimard’s head. Designer Eiko Ishioka’s set, made of sliding screens and a giant sweeping ramp, allowed for different scenes and settings to melt easily from one to another in Gallimard’s imagination as he sits alone in his jail cell, which is where we discover him at the top of Act 1. He introduces us to characters from his past, and he introduces us to Madama Butterfly, reenacting bits of his favorite opera to aid the story. An ensemble cast plays the supporting characters in both, with cheeky commentary for the opera bit. The play may be in Gallimard’s head, but he doesn’t necessarily call all the shots.

Opposite Lithgow was the production’s breakout star and most buzzworthy performance, BD Wong. Today Wong is famous as a part of the ubiquitous Jurassic Park and Law and Order: SVU franchises, among dozens of other credits. But unlike Lithgow, Wong was virtually unknown in 1988. He went through 5 months of auditions to land the role of Song Liling. The part that would mark his Broadway debut and would require a remarkable amount of range.

When Gallimard first meets the opera performer at the German ambassador’s house, he comments on the beauty of Madama Butterfly. Song, still in costume as a geisha, smacks him down:

“What would you say if a blond homecoming queen fell in love with a short Japanese businessman? He treats her cruelly, then goes home for three years during which time she prays to his picture and turns down marriage from a young Kennedy. Then, when she learns he has remarried, she kills herself. Now, I believe you would consider this girl to be a deranged idiot, correct? But because it’s an Oriental who kills herself for a Westerner – ah! – you find it beautiful.”

Lithgow and Wong acting opposite one another in M. Butterfly. Source: Billy Rose Theatre Division, The New York Public Library.

The next time they meet, Song is more demure, deferential. Gallimard’s desire is inflamed. He pursues, seduces, subdues. As his confidence in Song’s bedroom grows (always with the lights off) , it grows in other places too. Gallimard is promoted to Vice-Consul at the French embassy, where he has access to intelligence about America’s looming war in Vietnam and gets to offer his own hot take on the situation: “Orientals will always submit to a greater force.” As in the bedroom, so on the world stage, right?

The war and Gallimard’s affair are connected, of course, but not in the way Gallimard thinks. Throughout the affair, Song also has clandestine meetings with his communist case officer, Comrade Chin, played in the original production by Lori Tan Chinn (contemporary audiences will recognize Chin from Orange Is the New Black and Awkwafina is Nora from Queens, where she stars again alongside BD Wong). They discuss the war intelligence Song is collecting through Gallimard, and weigh the revolutionary ethics of procuring a baby to keep the scheme going. At the end of Act 2, Gallimard’s disastrous take on the Vietnam War gets him sent back to France, just as the political situation in China is shifting. After he’s left, Chin denounces Song as an actor-opressor and hurls homophobic insults during the Chinese cultural revolution, before sending him off on a final mission to reconnect with Gallimard back in France. Gallimard, in a mix of hubris and racism, cannot comprehend that he isn’t the Pinkerton of his saga, Song is Pinkerton. Gallimard is a bug caught in a honey trap, a butterfly under a pin. He is Cio-Cio-San, Monsieur Butterfly; M. Butterfly for short.

Hwang included a more subtle nod to Puccini (and Belasco, by extension) in the script of M. Butterfly, in the transition from Act 2 to Act 3. It’s a staged transition, just like in the opera and play. But in Hwang’s play, we don’t see Cio-Cio-San standing guard for Pinkerton. We see Song remove his makeup to appear fully as a man for the first time in the play. It might be hard for contemporary audiences to understand what this must have felt like in 1988. Many of us are steeped in drag culture and see queens taking off their makeup all the time. Many of us have seen (or at least know about) The Crying Game, which came out a few years after M. Butterfly on Broadway. Many of us know BD Wong as a man.

But that was not true in 1988. In 1988, Broadway audiences were introduced to BD Wong as a Chinese woman. And though it was eventually spelled out in the script that this woman was actually a man made up as a woman, that “spelling out” paled in comparison to the experience of actually seeing this intriguing woman take off her makeup and become a handsome young man in a suit; a handsome young man in a suit who testifies against Gallimard in court, forces him to reenact the night they fell in love, and then strips bare ass naked to drive his point home. That’s Song’s basic arc in Act 3 and it made an impression. In the show, Gallimard responds by committing suicide like Cio-Cio-San. In real life, Wong won a Tony Award for his Broadway debut.

BD Wong as Song Liling as Cio-Cio-San in M. Butterfly. Source: Billy Rose Theatre Division, The New York Public Library.

While Hwang and Wong gave their Tony acceptance speeches in New York, across the Atlantic in London a different production was also looking to Madama Butterfly for source material. Hwang and Wong didn’t realize it, but in 1988 they were already on a collision course with this British production, with the crash set to happen on Broadway.

We’ll cover that story next week in Part 3, when we’re going in on Miss Saigon.