Poster for Puccini's Madama Butterfly, depicting the show's violent end. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

This blog post is part IV in a series about the history connecting Madame Butterfly to David Henry Hwang’s Yellow Face. Check out part I here, part II here, and part III here. To check out the production of Yellow Face now playing on Broadway, click here.

The early 1990s had been a rollercoaster for David Henry Hwang. Within just two years he’d had his Broadway premiere with M. Butterfly, watched that show grow into a hit, won the first Tony Award ever for an Asian-American writer, and helped lead a protest against Miss Saigon for casting a white actor in an Asian role (a protest that almost got the blockbuster musical canceled). In short, a lot to process. So Hwang did what playwrights do when they have a lot to process: he wrote a play.

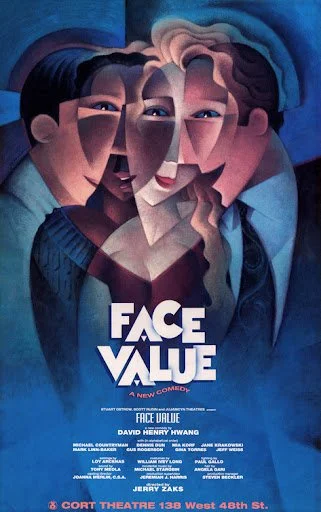

That play was Face Value, and expectations were high as the creative team assembled in late 1992. Director Jerry Zaks had won 3 of the last 4 Tony Awards for directing (including the premiere productions of Lend Me a Tenor and Six Degrees of Separation). The cast was stacked with talent, actors many of us would recognize from TV today: Mark Linn-Baker from Perfect Strangers, Jane Krakowski from 30 Rock, Gina Torres from Suits, Mia Korf from One Life to Live, plus BD Wong too. As a backstage comedy with a healthy budget and powerful producers, it had all the makings of a hit.

It all went terribly wrong. Face Value started previews on Tuesday, March 9, 1993, and was dead six days later after only eight performances; one of the biggest flops in Broadway history.

The poster for Face Value’s ill-fated Broadway production.

There had been signs that things were not going well during Face Value’s out-of-town tryout in Boston. For one, audiences weren’t laughing (never a good thing in a comedy). Reviews were dismal. A particularly pithy critic called the show “M. Turkey.” Then again, M. Butterfly hadn’t been rapturously received outside of New York either. So even with alarm bells ringing loudly, Face Value’s team had decided to forge ahead to Broadway anyway – with Hwang furiously working on rewrites the whole way.

The rest, as they say, is history. And by most measures, history is the only place Face Value exists today. The play was never published. Since it never officially opened in New York, there are hardly any records of its existence; just a handful of reviews from Boston. Which presented a conundrum when I decided to write about the play as the final part of this installment of this post series. Theatre history work is a bit like paleontology, trying to guess the living dimensions of something lost in time based solely on the scattered imprints it left behind. The fossil record here was pretty scarce.

Until I discovered an early draft of Face Value had made its way into the special collections of the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts. Obviously, I made an appointment to see it.

The New York Public Library for the Performing Arts, in her nighttime attire.

The Library for the Performing Arts is located at Lincoln Center, nestled behind the opera house, in the same building as Vivian Beaumont Theater. It is a gigantic collection of materials related to dance, music, and theatre, truly one of the gems of the New York Public Library system. If you have a New York library card, you should check it out. There’s tons of great books to check out, special exhibits, and my favorite part of the entire operation, the special collections location on the third floor.

Their special collections are non-circulating, meaning they can’t leave the library (they are special, after all). To view items there you have to make an appointment and view them on site, which is what I did. After checking in at the front desk, I was handed one of the few remaining copies of Face Value, sandwiched within an anonymous manila folder. The next three hours were a bit of a trip.

I should caution that the script I read was an early draft of a play that was relentlessly reworked and rewritten in Boston. I have no way of knowing how it compares to the production that actually played the Cort Theatre in 1993. Let me also caution that I don’t mean “trip” as an insult. What I mean is that Face Value is a play that goes many different places – some of them more successfully fleshed out than others.

The play revolves around a fictional Broadway musical, titled The Real Manchu, that casts a prominent white actor in an Asian role. Sound familiar? (If not, you can go back and read part 3 of this blog series). The show is at once over-the-top and oddly plausible, a satirical take not only on Miss Saigon, but also racist tropes that have long infected Broadway portrayals of Asians, since Madame Butterfly and before. Picture Jane Krakowski singing some of these lyrics from the show, and you’ll get the general idea: “Don’t get sentimental/ ‘Cuz he’s a crafty Oriental/ He’s inscrutable.”

The action takes place backstage for opening night of The Real Manchu, where a number of people have infiltrated in order to disrupt the show. There are Asian actors (Wong and Korf) disguised in whiteface so they can interrupt the show as a protest against yellowface, as well as white supremacist terrorists disguised as chorus members so they can protest Asians in general. Meanwhile, the show’s lead actor (Linn-Baker) is having a crisis of confidence and refuses to break character, even while trying to pursue an affair with his female co-star (Krakowski). None of this goes to plan, and it’s up to a harried stage manager (Torres) to try to keep everyone alive and on time for their cues.

Mark Linn-Baker and Jane Krakowski performing in one of the few publicity shots from Face Value. Photo credited to Joan Marcus, via New York Public Library. Source: The New York Times

It is madness. Everyone keeps assuming different costumes and identities. The Real Manchu’s actors have to try and prove they’re white to the white supremacists (who refuse to believe Broadway would allow yellowface in the 1990s). The Asian actors in whiteface have to then pretend to put on yellowface to try and save the actors who are actually white. Everyone drops character at the top of act two and discusses their personal feelings about the play. It all culminates in an “I am Spartacus” style climax where virtually everyone is disguised as someone else and starts removing costume items so their racial signifiers get mixed up and the white supremacists self-destruct.

Like I said, it’s a trip. Face Value’s central flaw is that it’s absolutely bewildering and very difficult to follow, as attested by the bad reviews and stunned silence in Boston. Hwang packed in a lot, and then didn’t have the time to fully iron it all out before the play opened in Boston (which is Hwang’s own position on how the doomed production went down, more or less). It’s clear that his intention was to create something greater (and funnier) than a stiff, preachy “message” play. The Asian actors have conflicting feelings about their activism. They each end up falling in love with the white actors who are performing in yellowface. The white actors, for their part, are complicated characters who grow over the course of the story. For a play about racial inequality, there’s a level playing field to the story: everyone is human, everyone is ridiculous, and everyone is struggling with the slippery and unstable concept of race.

As interesting as it was to read Face Value, the most important trace of the play today is not the manuscript I had the chance to read on the third floor of the Library for the Performing Arts. It’s in the other play David Henry Hwang eventually fashioned out of the failed comedy: Yellow Face.

Yellow Face had its New York City premiere at the Public Theater in 2007, almost fifteen years after Face Value’s disastrous Broadway run. It is also a comedy, one that very transparently mines Hwang’s personal life story. The protagonist is an Asian-American playwright named (drumroll please) David Henry Hwang – DHH for short. The play opens with a brief overview of the rollercoaster Hwang experienced in the early 90s, covering his Tony Award for M. Butterfly, the protests surrounding Miss Saigon (BD Wong and Cameron Mackintosh both appear), and eventually, the ill-fated Face Value, which is where things get interesting.

The Playbill from Yellow Face’s run at the Public Theater in 2007.

In the universe of Yellow Face, DHH inadvertently pulls a Miss Saigon. He unknowingly casts a white actor named Marcus as one of the Asian roles in Face Value. When DHH discovers this, he tries to cover his tracks, even encouraging Marcus to adopt a more Asian sounding stage name. That is, until Marcus is embraced by a group of Boston area Asian-American students, at which point DHH fires him and has him replaced by BD Wong for the show’s Broadway transfer. But it’s too late. Marcus establishes a career as an Asian-American performer, and it drives DHH crazy.

None of this actually happened in reality. Hwang and the real-world producers of Face Value did not hire a white actor in an Asian role. (It’s true BD Wong was called in as a last minute replacement when the show moved to Broadway, but the original actor he replaced was Dennis Dun, who’s Chinese-American). Though it’s presented as a chapter ripped from Hwang’s life, Yellow Face is actually something more complex and interesting than an autobiography.

Hwang has called the play a mockumentary. I like to think of it as a fun house full of mirrors; ones that reflect, remix, and distort actual historic events from the 1990s, all of which speak to the experience of being Asian-American in contemporary America. It takes many of our expectations about the now infamous Miss Saigon casting controversy and turns them on their head. What if David Henry Hwang was the same as Cameron Mackintosh? What if David Henry Hwang isn’t actually the hero of his own story? Honestly, these are brave questions to ask in an era rife with righteous anger, performative activism, and outrage (both real and imagined). It makes perfect sense that Yellow Face is having a moment on Broadway now. And it’s even more enjoyable to witness Hwang turn a professional failure into a career highlight, knowing that it was forged through self-awareness, patience, and tenacity.

There’s a long chain of events that connect David Belasco’s Madame Butterfly in 1900 to David Henry Hwang’s Yellow Face today. It’s easy to see Face Value as a trivial footnote within that arc, but I think it deserves more. Face Value pinpointed many of the themes that Yellow Face would more successfully expand upon, and also tackled the difficult subjects of race and representation with humor and empathy (as well as a moral compass). I don’t know that we would have the latter without the former. That alone makes it more than just a punchline.